‘Jouw paradijs, hoeveel ruimte is daar’

In “Jouw paradijs, hoeveel ruimte is daar”, I sketch out scenarios of the future from the perspective of a Diaspora jew. While not downplaying the complexity of Diasporic history, in this work I am researching the

In ‘Jouw paradijs, hoeveel ruimte is daar’, I sketch out scenarios of the future from the perspective of a diaspora ?ew. While not downplaying the complexity of diasporic history, in this work I am researching the relevance of diaspora, and ?ewish diasporic identity.

Diaspora, the scattering of a people, was firstly used to describe the dispersion of the ?ewish people after the Babylonian exile. Diaspora embodies movement, and has no specific land or territorium. The ?ewish State of Israel was established in 1948 (with the War of Independence, or as the Palestinians and other people call it, Nakba —catastrophe– as a result). Zionism was founded at the end of the 19th century, but from now on it really flourished. The new Israeli ?ews were called New ?ews, or Sabra’s. Sabra originates from the word Tzabar, which means cactus. ‘Sabra’ became a metaphor for the Israeli man: tough on the outside, delicate and sweet on the inside. The Sabra identity took shape both in the countrysides and the cities. The Palmach (an underground elite ?ewish defense organization) functioned as the foundation for the Sabra culture. The Sabra’s were expressing their identity in arts, language and ideology. Sabraism became a cultural phenomenon.This Sabra identity was -and still is- in sharp contrast with the diasporic ?ewish identity. According to the Zionists, The diaspora ?ew was weak and subjugated. The New ?ew was to be seen by the Zionists as the mythical image of the healthy, strong ?ew. The Sabra was represented and created in journalism, arts, and especially literature. Literature is fundamental in the creation of the Sabra culture and identity. But literature is not only fundamental for the Sabra’s. Literature forms an extraordinary part of the ?ewish culture as a whole. According to writer Amos Oz, besides literature, discussion and nuancing are essential in the ?ewish culture. As I see it, there is not much room for discussion and nuancing in the current Zionist politics, or in right-winged nationalistic politics in general, as one needs space to move from the one point of view to another. One needs room for debate. Space for discussion. This is why I think the diasporic identity and culture are of great importance. Diasporists feel at home both nowhere and everywhere. Diaspora is about movement. It is about living without boundaries (and both the fear and relief that this brings). The diasporic character is said to be questioning, investigative and curious.

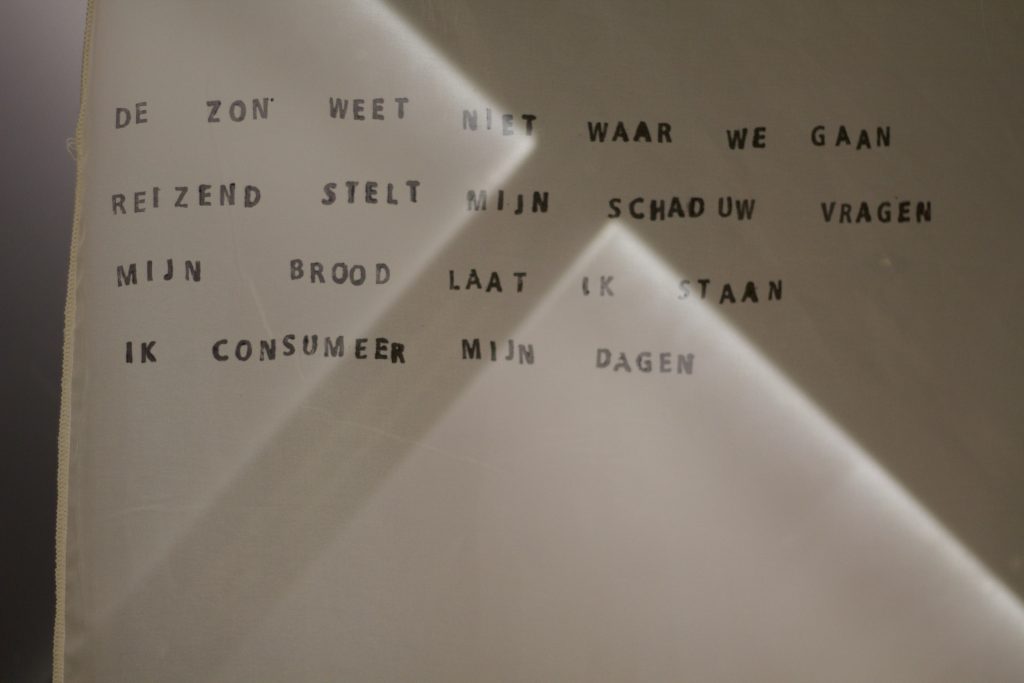

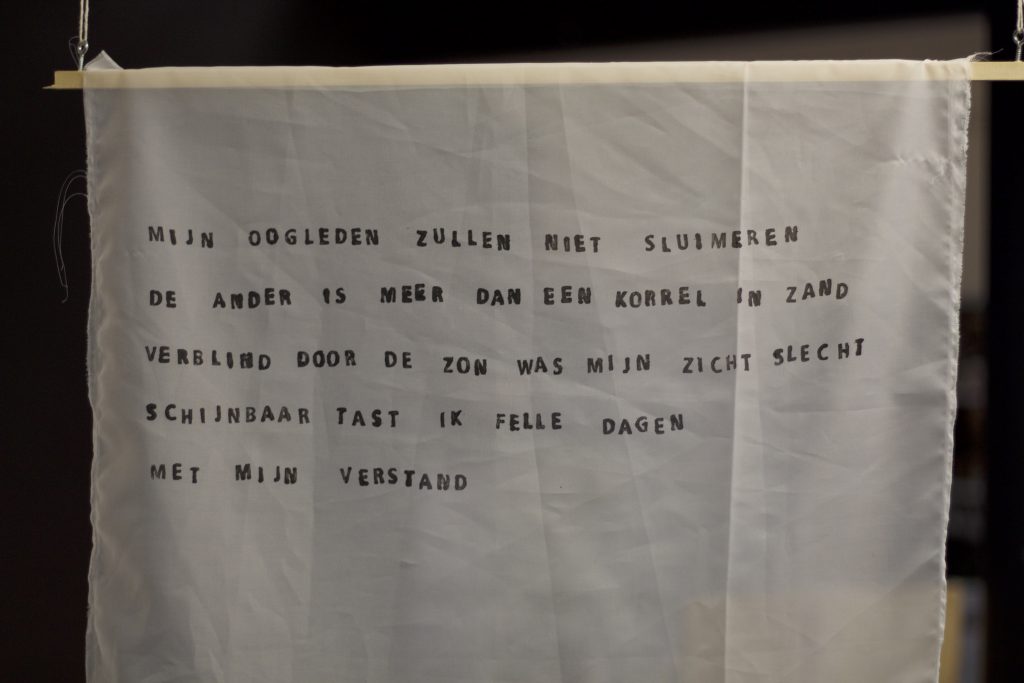

This work consists of poems, as I want to highlight the importance of literature. Furthermore, to envision new future diasporic stories, to work with time as a nonlinear phenomenon in the poems is essential. Diaspora itself is a beautiful example of the non-linearity of time: ?ewish people have been living, are living, and will be living in different time zones all over the world. And they have been moving, are moving and will be moving constantly over time and place. Additionally, as the Torah was not written in chronological subsequence, it is perfect material to work with. I used the Shemot (the second book of five that forms the Thora. The Shemot covers the diaspora) as a text to write the poems with. By shuffling, erasing, re-writing text of the Shemot, I created the poems.

During the exposition of this installation, the poems were spread through a room. They resembled walls, yet they were not fixed; you could lift, displace and move them. In the performance that was part of this work, the poems were spread through a room. They resembled walls, yet they were not fixed; you could lift, displace and move them.The audience could wander and walk with me from one poem to another. By telling stories about ?ewish history, I was functioning as their tour guide in this future script.

de zon weet niet waar we gaan

reizend stelt mijn schaduw vragen

mijn brood laat ik staan

ik consumeer mijn dagen

mijn oogleden zullen niet sluimeren

de ander is meer dan een korrel in zand

verblind door de zon was mijn zich slecht

schijnbaar tast ik felle dagen

met mijn verstand

wie woont waar

klanken overschreeuwen elkaar

de aarde verdroeg en draagt

dit sojourner assemblage

niet zonder blessures

overtuiging weegt zwaar

het landschap maakte rap een wende

men at matzos ongedurig

en brak deuren van de tenten

de vlakte smaakte toch wat zurig

in de schaduw van gebroken huizen

liep het erfgoed met gekromde rug

het voelde zich unheimisch en

besloot: ik kom niet terug

offeren via vrije wil

die ceremonies leven al tijden

maar in dat altaar is het te stil

vooral ‘s avonds zou ik het mijden

passeer de winkelstad

zwerf het land uit

smijt het stof de aarde af

de lichting reist af naar noord

streek neer in een up-to-date gebied

alles is precies op tijd

toekomst lag in het verschiet